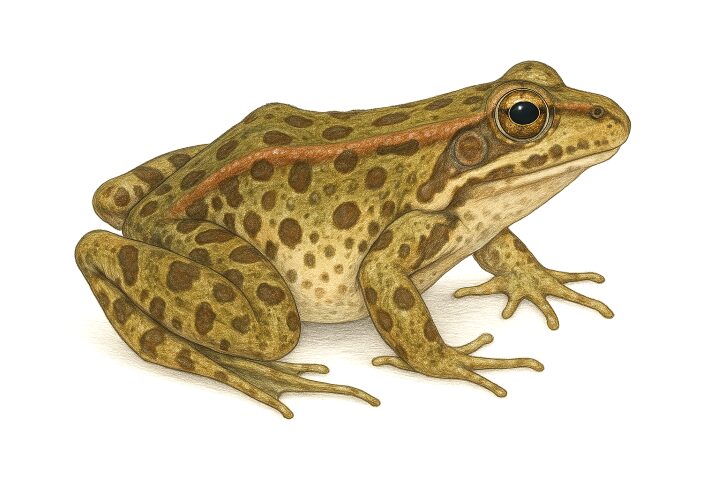

The Oregon Spotted Frog is a rare and fascinating amphibian that’s become a conservation icon in the Pacific Northwest. Known for its bold black spots and striking reddish coloring, this frog has quite a story. Once common in wetlands from British Columbia to Northern California, it’s now considered threatened, with habitat loss playing a big role. If you’re lucky enough to see one in the wild, you’ve spotted something truly special.

Size & Physical Appearance

Adult Oregon Spotted Frogs range from about 1.75 to 4 inches long. Females tend to be noticeably larger than males, sometimes by more than an inch.

Their skin is smooth and moist, typically a rusty brown or olive green, with plenty of small black spots with light-colored borders on their backs and legs. As they age, many develop a more intense reddish or orange hue on their legs and underbellies — this is especially noticeable in breeding females.

Younger frogs (juveniles) are usually duller in color and lack the deep red tones of mature adults.

Habitat and Range

Oregon Spotted Frogs love the water. They’re almost always found in or near permanent, slow-moving water like marshes, ponds, lakes, and beaver-dammed wetlands. Look for areas with lots of aquatic vegetation — that gives them good cover from predators and a place to lay their eggs.

Their current range is pretty limited. They’re found in parts of Washington, Oregon, and a small corner of northern California. Historically, they were much more widespread, but urban development, agriculture, and the draining of wetlands have shrunk their habitat. They usually live at low to moderate elevations, below 4,000 feet.

Diet

These frogs are not picky eaters. They’ll snatch up a variety of small invertebrates — think insects, spiders, beetles, snails, and worms. Tadpoles are mostly herbivorous, feeding on algae and decaying plant material in their watery homes.

What’s interesting is how active they are during the day compared to other frogs. That makes it easier to spot them hunting or sunning themselves (a behavior called basking).

Lifespan

In the wild, Oregon Spotted Frogs can live around 4 to 8 years, though many don’t survive to adulthood due to predators and changing conditions. In captivity, they may live slightly longer, but this species is tricky to keep and breed outside its natural habitat.

Identification Tips

This frog can be confused with the Northern Red-legged Frog, which shares part of its range. Here’s how to tell them apart:

- Spots: Oregon Spotted Frogs have round, dark spots with light borders. Red-legged Frogs usually have less defined markings.

- Color: Oregon Spotted Frogs turn redder with age, especially on the legs and belly.

- Eye orientation: Their eyes point outward, not forward — this gives them a different “face” than many similar frogs.

- Dorsolateral folds (ridges along the back): These folds are lighter colored and distinct in the Oregon Spotted Frog but usually less prominent in other species.

If you’re trying to ID one in the field, your best bet is to observe the color of the belly and limbs and look for those telltale black spots with pale borders.

Fun Fact

Despite their name, Oregon Spotted Frogs are excellent swimmers and spend far more time in the water than many other frogs. Unlike some amphibians that only use water during breeding season, these frogs are often fully aquatic. In fact, if you see one on land too long — something’s probably wrong.

Why They Matter

The Oregon Spotted Frog is more than just a cool-looking amphibian — it’s a key indicator of wetland health. Protecting them means protecting the entire ecosystem that so many plants, birds, and other animals rely on.

If you ever spot one in the wild, enjoy the moment and snap a photo (from a respectful distance). And if you’re in the Northwest and want to help, consider volunteering with local wetland restoration efforts — every bit helps keep species like this around for the next generation.